This week I had a curious misunderstanding. I was chatting to a woman who’s a similar age to me, and she mentioned that she was ‘going up to Cheshire to do a bit of Granny duty’. As she said this, I imagined her with an elderly mother. It was only as the conversation progressed amidst considerable confusion, that it dawned on me that she is the Granny—and the recipient of the care is a child. This says something about where I am in life. My four children are all adult, but as yet, grandchildren haven’t impinged. The opposite end of the generational scale has, however, been a big part of my world for the past couple of years.

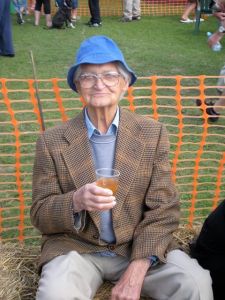

Sadly, that phase came to an end four days ago when my father-in-law, Frank, died. It was not exactly unexpected as he was ninety-seven and frail, but it was nonetheless sudden and we, together with the rest of the family, are still coming to terms with the loss. He lived with us for fifteen months up until last September, and whilst an unconventional start to our married life, we gained so much from that time.

I’m grateful for what Frank taught me. ‘Old age is not for sissies’, he would say often, quoting Bette Davis. And I saw how true that was in his case. Failing vision, hearing and memory all conspired to diminish his grip on life and to make him feel vulnerable. Last year, I realised to my astonishment that I’d lived well into my fifties with virtually no exposure to this world of extreme old age. My own parents didn’t live that long and so it was all new to me. There was a lot to learn about fragile skin, special support shoes, memory lapses, bedrails, podiatrists, hearing aids, and many, many other things. It was challenging for all of us, at times, but it was also a privilege to be exposed to it because it’s so often hidden away. I stepped into a world that moves at a different pace, and which had previously passed me by. And it wasn’t just me. My children, too, learned a lot and I’m grateful that in the midst of their fast-moving lives, they were able to be patient.

Despite his trials, Frank kept his sense of humour. Often, we’d sit together at lunchtime with our bowls of soup and there would be long, companionable silences. But at other times he’d come out with wry, random memories. One of my favourites was of being a sergeant major in Rangoon at the end of the war. The officers would disappear into their office at nine in the morning and he would then be responsible for eighty soldiers in the raging heat. “If I let them go,” he said, “then they’d go straight to the brothels and get syphilis.” So he marched them up and down for as long as he dared before they all started passing out. It was a fine balance and he never did explain how he resolved it. There are many things that we’ll now never know. He told me in a recent lucid moment that when he was about seven he would go by bus from Walsall to Birmingham with his mother on Saturday mornings. She took him to see a doctor every week for months but he couldn’t remember why.

All kinds of childhood memories would pop up and even the mundane details revealed a different world. It had never occurred to me to wonder what people did before they had dustbins. But Frank remembered people piling their rubbish up and then contacting the council who would send round a couple of men with wheelbarrows. They’d load up the rubbish, wheel it down the alley and put it into a cart.

Sue’s visit from Australia

One of the difficult things about these past few years with Frank was realising that we simply could not solve his problems. We did what we could to help, but in the final year he was in a lot of distress and repeatedly said that he wanted to die. It was very hard for him. Hard too for his children overseas—Sue and Barry in Australia, and John in South Africa. Sometimes the confusion could be positive, though. About a month ago, he had his ninety-seventh birthday but kept telling everyone, ‘I’m a hundred, today.’ After a few attempts at correcting him we realised that there was no point. He’d forget what we said anyway, and if he wanted to celebrate being a centenarian then that was just fine with us. I’m so glad now that he was able to have his ‘hundredth’ birthday.

One of the many things I value, is that he rekindled my interest in poetry. Despite a lifelong love of words, I’ve been put off poetry by the obsequious tones in Radio 4’s ‘Poetry Please’. Frank, however, could recite reams of verse right up to the final weeks of his life. And he did it beautifully, with no hint of obsequiousness. ‘Cargoes’ by John Masefield, ‘The Vicar of Bray’, and many others were all delivered in his lovely voice, laying bare the sensitivity locked into an old man’s body. That’s a memory I will treasure and the poem that he loved above all others is ‘Trees’ by Joyce Kilmer:

I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree.

A tree whose hungry mouth is prest

Against the earth’s sweet flowing breast;

A tree that looks at God all day,

And lifts her leafy arms to pray;

A tree that may in Summer wear

A nest of robins in her hair;

Upon whose bosom snow has lain;

Who intimately lives with rain.

Poems are made by fools like me,

But only God can make a tree.

You were no fool, Frank, though you certainly weren’t averse to a bit of silliness. I know, too, that you weren’t a religious man. But you did say that if anything could convince you that there’s a God, then it would be the sight of a magnificent tree. Wherever you are now, then I wish you peace after your long life, and am grateful for the time we spent together. Thank you too for letting me share your ‘hundredth’ birthday cake.

What a lovely tribute to Dad – just lovely Lynnie

LikeLike

Wonderful! Intuitively ‘spot on’.

Love to you both.

Helenx

LikeLike

A perfect tribute Lynn to a man I never met but felt I had by the time you had written about him so sympathetically over the last couple of years.

RIP Frank.

Gimma

LikeLike

That is a very moving piece Lynn. Trees are so important in our lives and so comforting too when death occurs.

LikeLike

Lovely tribute Lynn. Thanks.

LikeLike

A wonderful tribute to a man loved by his family.mxx

LikeLike